Fieldnotes: 3D Printshow London

While I have been aware of 3D printing, my interest in it has been somewhat casual given my other research commitments. So when I was shoulder tapped to help out with some field interviews at a 3D printing expo in London it was a great excuse to investigate the technology further.

The 3D Printshow is an expo organised in cities around the world – London, Paris, New York, Berlin, Dubai, Mexico and others – to showcase applications and developments in 3D printing, or additive manufacturing as it is also known. The London event just happened to align with me being in the UK doing some fieldwork of my own. The show ran over three days at the beginning of September, catering to everyone from your simple back-room tinkerer to industry heavyweights. Held in a large display space in the heart of the City of London, the show was packed with stands, exhibits and talks that ran throughout the three days.

The research was part of an exploratory project funded by University of Wollongong’s Global Challenges Program investigating the potential of 3D printing in reenergising manufacturing in the Illawarra, being undertaken by Dr Thomas Birtchnell and others.

Thomas had arrived in London with a Global Challenges pull-up banner and a stack of leaflets. I met him at the start of day one at our booth to help set up. The booth was shared with another organisation, Tech for Trade, which focuses on ‘bridging the divide between emerging technology and international trade and economic development’. Thomas had done some work with William Hoyle, director of the organisation, and together they’d written a book – 3D Printing for Development in the Global South – which was soon to be published, so it was also an opportunity to promote this. Tech for Trade were also promoting one of their initiatives, the Ethical Filament Foundation, which had been working on producing filament – the (usually) plastic that is used in the printing process – made from recycled materials. With the assistance of Indian fair trade startup Protoprint, the plastic is sourced from waste-pickers in Pune, India and converted on-site into 3D printing material. This new product garnered a good deal of interest from those visiting the expo.

Over the expo’s three-day run, many thousands of people visited. The floor always seemed to be busy. Our task for the Global Challenges research was to simply strike up conversations with people about their thoughts and interests on 3D printing. That was not difficult as people were generally enthusiastic to chat.

There appeared to be a surprisingly wide range of people visiting the show. For example I spoke with people from industry, some investigating how they might incorporate 3D printing into their business, as well as those already using it but keeping abreast of new developments. One guy was from the largest plastics supplier in China, investigating the implications for their supply business. There were a number people from small and medium businesses also doing investigative research, and a couple of investors looking for opportunities to fund emerging startups. I also spoke to a number of enthusiasts who had been experimenting with the technology for a number of years and finding ways to apply it to smaller-scale projects, whether that was in developing a product of their own, or using it at a community level to introduce kids to computers and programming. Then there were the people ‘off the street’ – people who didn’t know much about 3D printing but were curious. There was a retired doctor and his wife just “checking it out”; a physiotherapist who was just interested to find out what it was all about; a pair of students who were looking for a reasonably priced printer to play around with.

What struck me about the show over the three days was the positive buzz that permeated the room. People seemed genuinely excited about 3D printing and its application. I spoke with one guy who was a regular visitor to such events and he admitted that the current one was bigger than the last and the vibe better. As Thomas and I discussed the show we imagined it was a bit like the early days of computers, or perhaps the internet, infused with a feeling of emergent potential – though no one was quite sure exactly what that was. And this was a question I put to people as I talked with them: what do you think we’ll be able to do with 3D printing? The answers were all similar: you can design and print your own customised things, or make replacement parts for broken equipment. These kinds of responses weren’t surprising as it’s how the technology is commonly promoted. But while those are obvious starting points it was difficult to tease out much more than this.

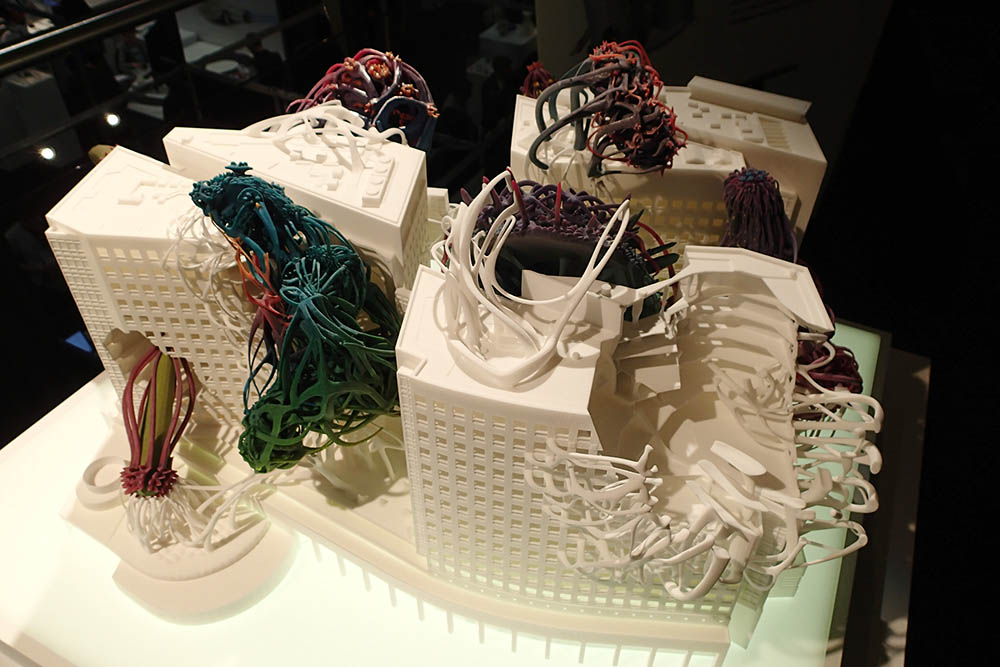

With any emerging technology it can be difficult to actually imagine both the applications and implications of its use. And that is where 3D printing seemed to be at that moment. Certainly there were scores of small brightly coloured plastic knick-knacks (like cracker toys, Thomas and I joked) that had been 3D printed: phone cases, figurines, busts, 3D puzzles. But these seemed rather gimmicky. Going to a couple of industry talks dug a little deeper into the production potential, bringing imaginative agency to real-world application: customised production of therapeutic devices such as splints, braces, artificial limbs, or production of fashion designs not able to be produced by traditional processes. Many of the applications, however, were only experimental projects, and still expensive to produce. But the experimentation continues, and within the expo there were examples of 3D printing being applied across all scales, from architecture, earth, metals, food, and right down to the biological cellular-level.

What struck me from a more theoretical standpoint is how 3D printing allows us to manipulate matter in a way we haven’t been able to do so before. As Chris Anderson (ex WIRED magazine editor) has said, ‘atoms are the new bits’. He was commenting more on industrial innovation, but this idea translates more broadly. What 3D printing allows is for us to transfer ideas between a computational, virtual space and the material world. This gives us the ability to use more complex processes to compute and model objects and then give them form in almost any material. It also opens up a range of possibilities in what can be produced – objects are able to be fabricated that we’ve previously been unable to produce, let alone imagine. In that sense 3D printing both allows us – and indeed invites us – to extend our imagination as to the kinds of objects we are able to produce. For those concerned with understanding implications of contemporary ‘post-natural’ materiality 3D printing appears to both allow us to realise culturally novel forms but also brings possibilities of responding to post-natural conditions. For me that was the real takeaway.

But as to the more practical applications of additive manufacturing, it appears that we don’t yet quite know what can be done with it. The expo showed there are a range of innovators and startups trying new things across a wide range of application but only time will tell what ideas ‘have legs’. However, as Thomas and William’s work shows, the larger-scale implications of technology – broader social, political, economic impacts – require examination.